TImes Select, the online part of the New York Times which is generally hidden behind a subscription wall, is free all of this week. It's worth a look if you're in search of yet another form of distraction, and with the mid-terms today, this is a good week to be able to avail of it.

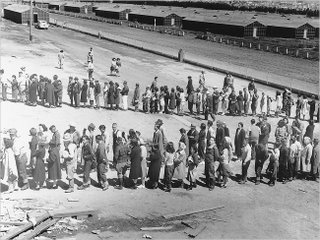

One piece I'd recommend is this article on a cache of over 800 newly discovered Dorothea Lange photographs, from the period in the 1940s when tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans were rounded up and sent to internment camps on the west coast of the U.S. as the war with Japan escalated. Lange's photographs were impounded by the government soon after they were taken and have been in the National Archives until now; W.W. Norton has just published 100 of them in a book called Impounded. The book's co-editor (with Linda Gordon) describes the kind of America this was, as families were ordered at gunpoint into horse stalls and shacks, where they were interned, in many cases for years afterwards, in the intense California heat. An editorial from the L.A. Times read: “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched — so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents — grows up to be Japanese, not an American.”

Lange had actually been employed by the government to document the process, presumably to show that detainees were not being mistreated. But at most of the locations she visited, she found her work being censored by government officials even as she tried to create it; at one camp, she was forbidden from taking photographs of wire fences, watchtowers, armed guards or anything like that. The photographs then disappeared almost as soon as the commission was completed.

To my shame, this is a period of history of which I only really became conscious last year, when I was researching the life of Isamu Noguchi, one of the most famous sculptors of the 20th century, who was Japanese-American. By the 1940s, he lived an artist's life in New York, had designed many high-profile pieces including the entrance to the Rockefeller Centre, and was a revered collaborator with the choreographer and dancer Martha Graham. In response to the growing anti-Japanese sentiment in the U.S., Noguchi established a group of writers and artists calling for democracy and travelled to California to oversee a documentary about the internment. He left California lest he himself be interned, but when he found, back in New York, that his efforts to influence government officials were failing, he decided to become a voluntary internee at the Poston camp, located on an Indian reservation in Arizona. He designed parks and recreational areas within the camp - including, tellingly, a cemetery - but soon realised that officials had no intention of implementing them. And when he applied for release, he was deemed a "suspicious person" due to his involvement with the artists for democracy group. He was forced to remain on for several months, and investigated by the FBI after his eventual release.

I was shocked to learn that this had happened to Japanese-Americans, in their hundreds of thousands, in the U.S. Looking at the country today, of course, I don't know why I was shocked. Noguchi was one of the lucky ones; he returned to his life in Greenwich Village, to exhibitions, acclaim and friendships with influential artists and the celebrities of the time. Other Japanese-American internees had less to look forward to. As the essay accompanying Lange's photographs makes clear, both the lives led by internees within the camps and the lives to which they returned after their release were often tragic.

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

Times Select

Posted by

hesitant hack

at

7:14 AM

![]()

Labels: new york times, photography

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

thanks for the links.

Hey, sorry to use comments for this but I've been trying to e-mail you and it keeps being bounced becuase your mailbox is full! Thought I should let you know. Could you drop me a line at my work e-mail address?

-Anna

Post a Comment